China’s Violation of the Right to Adequate Food of Filipino Fisherfolk in the West Philippine Sea (WPS) based on the Philippine National Marine Interest as stated in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) (Originally Published 2021/09/15)

Aurea G. Miclat-Teves

President, Peoples Development Institute

Convener, Koalisyon Sa Karapatan sa Sapat na Pagkain

Introduction:

Established in 1990, the Peoples Development Institute (PDI) is a nongovernmental organization whose mission is to establish self-reliant communities through people’s initiatives. PDI’s strategic intervention focuses on asset reform and economic support services coupled with social infrastructure building. PDI implements programs with three critical components: First is the access to resources (e.g. Land, water, marine and other natural resources, etc.) by farmers, fisherfolk and indigenous peoples, or IPs; second is providing support services to make their lands/resources productive; and lastly, organization building that is complemented with training and education to prepare key members of the communities to become leaders and entrepreneurs, actively participating in local governance.

PDI believes in the primordial importance of asset reform from land rights and our rights to our maritime regimes. Since 1991, PDI has established partnerships and successfully formed people’s organizations or POs, especially those that fight for farmers’, fisherfolks’ and indigenous people’s rights. In 2015, together with some POs, PDI became instrumental in building the PKKL, or the Pambansang Koalisyon ng Karapatan sa Lupa (National Coalition for Land Rights). PDI has been actively advocating for our fishers’ rights in the West Philippine Sea (WPS) since 2016 and later formed BIGKIS, the federation of fisherfolk in Zambales and Pangasinan.

In 2012, we saw the aggressive entry of the Chinese into the WPS and other economic fields such as mining and other investment prospects in Central Luzon, especially in Zambales. This was being done in partnership with the local government authorities and officials of state agencies. The opening of business opportunities for foreign and local investors directly affected the fishing rights of the fisherfolk, especially in Zambales and Pangasinan, whose traditional fishing grounds in WPS were being encroached upon and harmed, especially by the Chinese.

Chinese vessels blocking the entrance to Scarborough Shoal. The group of ships in the right picture had come from the waters off Palawan province.

The National Maritime Claims of the Philippines under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS)

National Maritime Interest

The Philippines is an archipelago situated about 600 miles (966 Kilometers) off the southeastern coast of the Asia Mainland and lies arc from the southern tip of Taiwan, to the northern parts of Borneo and Indonesia approximately 1,500 miles (1,850 kilometers) long and about 600 miles (966 kilometers) wide. It is bounded by the South China Sea on the west and north, the Pacific Ocean on the east, and the Celebes Sea and the coastal waters of Borneo on the south.

The archipelago consist of 7,107 islands scattered over some 500,000 square miles (1.3 million sq. km.) of oceanic water. It has a total land area of 115,850 square miles (300,050 sq. km.), and a coastline length of approximately 10,850 statute miles (17,461 km.).

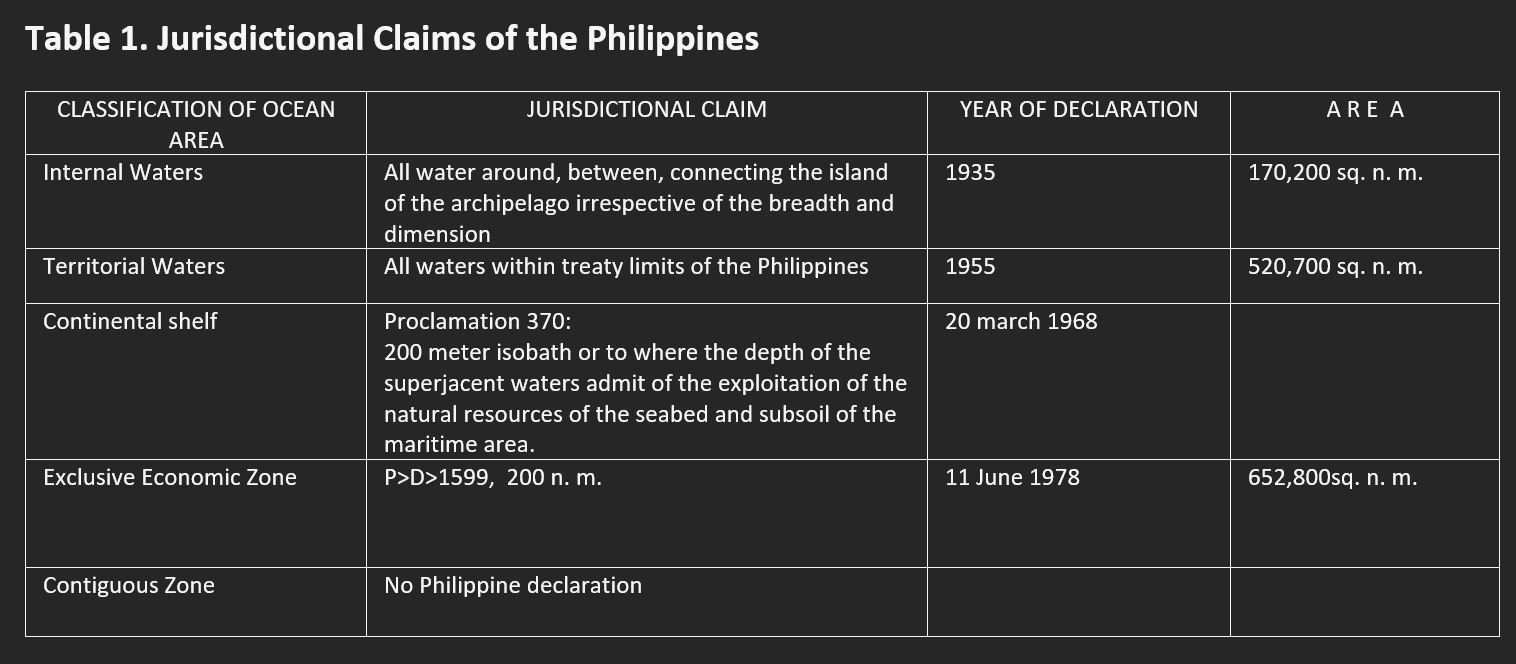

Its land, waters and people form an intrinsic geographical, economic and political entity, and historically had been recognized as such. The government of the Republic of the Philippines has considered its unique configuration in drawing up its official position on the various Law of the Sea Regimes. Table I shows in brief the Philippines jurisdictional claims.

1.) Jurisdictional Claims of the Philippines

A. Internal Waters

All waters around, between and connecting the different Islands belong to the Philippine archipelago, irrespective of their width and dimension, and are necessary appurtenances of its land territory, forming an integral part of the national or inland waters, subject to the exclusive sovereignty of the Philippines. ( Source: Article 1, 1987 Philippine Constitution)

B. Territorial Waters

As provided for in Article I of the 1987 Philippine Constitution, the Philippine claims a territorial sea zone wherein she exercises absolute sovereignty. This sovereignty extends to the airspace above, and the seabed and subsoil below the territorial seas

C. Continental Shelf

The Philippines claims a continental shelf till the two hundred (200) meters Isobath or to where the depth of the superjacent water admits of exploitation of the natural resources of the seabed and subsoil of the submarine area.

The Philippines will exercise sovereign exclusive rights but only over the mineral and non-living resources and sedentary living organisms found in the shelf. The freedom of navigation and overflight, the laying of submarine cables and pipelines will be respected in the zone.

D. Exclusive Economic Zone

The Philippines declared an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) on 11 June 1978 through President Decree No. 1599. The zone extends for 200 nautical miles (370 km) from the baselines from which the territorial sea is measured. Within this area of the zone, the Philippines will exercise (without prejudice to the country’s right over the territorial sea and the continental shelf) specific types of rights particularly:

- 1.1. “Sovereign rights” for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the living and non-living resources of the zone which can be found in the subsoil or superjacent waters. The same rights cover associated activities for the resources exploitation on the area such as the production of energy from tides and current.

- 1.2. “Exclusive jurisdiction” over the establishment of artificial island offshore and other structures, the preservation of the marine environment, and scientific research.

- 1.3. Such other rights recognized by internal law

The rights of the other states, however, are recognized with respect to navigation and overflight, the laying of cables and pipeline, and the other international lawful uses the sea regarding navigation and communication.

Consequently, no state or person may explore or exploit any of the resources in the zone, conduct research or drilling, construct and operate any offshore structures and terminals, or engage in any activity which may pollute marine environment, or undertake any other activity contrary to the sovereign rights of the country within the said area without the consent of the Philippines.

There are also provided specific penalties for violators of the said law in the zone, including the seizure of vessels and the equipment use in violating said laws.

In order to appreciate the implication of the EEZ regime, it is necessary to relate and contrast this particular regime with other jurisdictional regimes which the Philippines has established in the adjacent and internal marine areas of its territory.

E. Archipelagic Waters

Archipelagic Principle. The Underlying basis of the Archipelagic Principles is the unity of land, water and people as single entity. The necessity of maintaining and preserving this unity is important so that the archipelago may not be splintered in to its composite islands with the consequent fragmentation of the nation and the state itself.

Instead of arbitrary boundaries, straight baselines are drawn connecting the outermost points of the archipelago. The waters enclosed within the baselines, as in the case of continental state are defined as internal waters.

- An archipelagic state whose component islands and other natural features form an intrinsic geographical, economic and political entity and historically have or may have been regarded as such, may draw straight baselines connecting the outermost points of the outermost islands and drying reefs of the archipelago from which the extent of the territorial seas of the archipelagic state is or may be determined.

- The waters within the baselines, regardless of their depth or distance from the coast, the seabed and the subsoil thereof, and the superjacent airspace, as well as their resources, belong to, and are subject to the sovereignty of the archipelagic states.

- Innocent passage of foreign vessels through the waters of the archipelagic state shall be allowed in accordance with its national legislation, having regard to the existing rules of international law. Such passage shall be through sea lanes as may be designated by the archipelagic state.

It must be noted that the Philippines at the earliest, in 1958, had advocated the inclusion of the Archipelagic Principle as a concept of International Law.

2.) summary of overlapping boundaries

A. Territorial Sea

The Philippines territorial sea overlaps in the north with Taiwan’s EEZ while in the south, Indonesia’s baseline intrude into the Philippine territorial sea. The extended territorial sea claimed by the Philippines is based on historic rights and legal title.

B. Continental Shelf

Part of the Philippine continental shelf off the southern tip of Palawan in the direction of the Kalayaan Island has been enclosed in a continental shelf map published officially by Malaysia. In other parts of the archipelago, the Philippines claims seabed areas up to 200 nautical miles (370 km) measured from the baselines. The same problem of overlapping claims should be anticipated as in the delimitation of the Philippines EZZ.

C. Exclusive Economic Zone

The Philippines’ 200 nautical-mile (370-km.) Exclusive Economic Zone overlaps with that of Taiwan, Indonesia, Vietnam, Mlaysia, Palau and the Paracels. The People’s Republic of China claims the Paracels. The Paracels is 345 nautical miles (about 640 km) from the Kalayaan Island Group’s Pag-asa Islands.

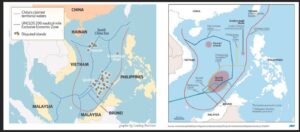

The Territorial Issues in the West Philippine Sea (South China Sea)

Lying south of the Paracels is a group of about 100 islands, shoals and reefs, generally known as the Kalayaan Island Group (Filipino) or Spratlys (Truong Sa to Vietnam, Nansha to the Chinese and Taiwanese, and Kalayaan to the Philippines). There has been conflicting or overlapping claims of ownership of the islands among Vietnam, Philippines, China, Taiwan, Malaysia and Brunei. The Chinese (both China and Taiwan) claim ownership of the entire Spratlys chain. Vietnam claims a large area. The Philippines claim is limited to the area enclosed by the limits defined in Presidential Decree 1596. Malaysia and Brunei, on the other hand, claim several features in the southern region of the Spratlys.

Ownership of the Spratlys has been assumed by different dynasties and governments of both China and Vietnam, but often without the awareness of the other claimants. The current dispute started in July 1933 when France, on behalf of its protectorate, Vietnam, occupied nine islets of the Spratlys and placed them under French sovereignty. China, and also Japan, protested the French move. Vietnam and China have since been the most bitter rivals in the Spratlys.

Taiwan’s active claim to the islands started in December 1946 when a naval task force visited the islands. The islands were subsequently placed under the administration of the Navy in March 1947. In April 1952, Taiwan and Japan signed a peace agreement in which Japan repeated its renunciation of all right, title and claim to Taiwan and the Spratly Islands, previously articulated in the San Francisco Peace Treaty of 1951. Japan occupied the islands in 1939 but withdrew in August 1945, after its surrender to the Allied Powers.

The Philippines was the first to assert title to the territory after Japan's 1951 renunciation. In 1956, a Filipino, Tomas Cloma, issued a “Proclamation to the Whole World” asserting ownership of 33 islands, sand cays, bars, coral reefs and fishing grounds.. On June 11, 1978, the Philippine government officially declared sovereignty over part of the disputed territory, roughly duplicating Cloma’s claim. But as early as 1947, the Philippines Secretary of Foreign Affairs demanded that the territory which was occupied by Japan during World War II be awarded to the Philippines[1].

Malaysia, in 1980, issued an official continental shelf map which showed the boundary limits enclosing some portions of the Spratlys and even some Philippine islands in the area close to Palawan province.

China asserts sovereignty over almost all of the strategically vital waters in the face of opposing claims from its Southeast Asian neighbors, and has rapidly turned reefs into artificial islands capable of hosting military planes and warships.

National Marine Interests of the Countries Involved in the Maritime Dispute

South China Sea is rich in marine life, hydrocarbons and natural gas. There is also trillions of dollars worth of global trade that passes through these waters. The Kalayaan Island Group (Spratlys) are mostly coral reefs, which allow only sparse growth of mangroves, shrubs and stunted trees, and can hardly support human habitation. But ownership of the islands will enable a claimant state, in the light of developments in international law, to declare jurisdiction and/or sovereignty over wide areas of the ocean.

The waters off the islands teem with marine life especially demersal fish and tuna. The Philippines' Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) estimated that 1 metric ton is harvested per day during summer in the Kalayaan Island Group (KIG) mainly by using otoshi-ami, a type of fishpen, and deep handlining. Taiwanese longline and trawlers also fish in the area.

Petroleum and gas of considerable amount are believed to be trapped in the Kalayaan seabed. This belief stems from the fact that East Asia, of which the South China Sea basin is a part, is a rich diversity of tectonic processes and relatively high sedimentation rates that have resulted in a combination of geological conditions in some places which are conducive to petroleum formations and accumulation. Most of the petroleum-bearing formations thus far identified are in sedimentary basins of tertiary origin and deposition, and the KIG lies in a geological belt of the same characteristics such that petroleum speculation has been intensive.

Some UN- and private company-sponsored surveys revealed structures potentially favorable for petroleum accumulation in the vicinity of the KIG. Recently published analyses of data from the Reed Bank drilling operations support the notion that it is an area that is geologically contiguous with the Nido reef complex, which yielded petroleum and gas in commercial quantity. The potential oil reserves of the Reed Bank was estimated at 5.4 billion barrels of natural gas, according to a report by the US Energy Information Administration. Other KIG seabed areas fall abruptly to 1,000 to 3,000 feet such that development is considered either technically unfeasible or commercially unprofitable at present. Technological development, however, does not preclude the possibility that petroleum production may become commercially profitable in the future.

As mentioned above, the KIG or Spratlys also straddle one of the world’s busiest sea lanes, and lie within the air routes of Borneo, Indonesia, Vietnam, China and the Philippines. The strategic importance of the area for defense and security, and maritime navigation and overflight has generated interest not only from the claimants to the area but also from major powers such as US, Japan, and Russia, and now China.

Ownership of the islands would undoubtedly represent gains for a claimant’s economy, defense and security. Hence, the varied attempts of the claimants to gain control of the disputed area.

(Asia Pacific Rim Fishing Grounds, Focused on the West Philippine Sea, Scarborough Shoals)

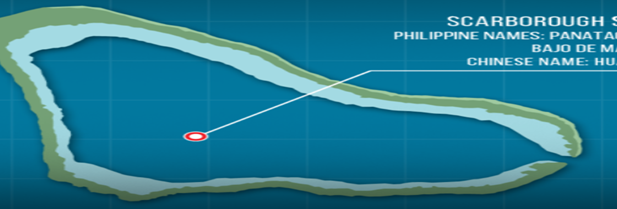

The Scarborough Shoal locally known as Panatag Shoal

A. Geography

Scarborough Shoal is Panatag Shoal in Philippine maritime claim and is commonly called Bajo de Masinloc. It forms a triangle-shaped chain of reefs and rocks with a perimeter of 46 km (29 mi). It covers an area of 150 km2 (58 sq mi), including an inner lagoon. The shoal's highest point, South Rock, is 1.8 m (5.9 ft) above sea-level at high tide. Located north of it is a channel, approximately 370 m (1,214 ft) wide and 9–11 m (30–36 ft) deep, leading into the lagoon. Several other coral rocks encircle the lagoon, forming a large atoll.

The shoal is about 270 km west of Subic Bay and is within the EEZ of the Philippines. To the east of the shoal is the 5,000–6,000 m (16,000–20,000 ft) deep Manila Trench. It is also near Palauig, Zambales on Luzon island in the Philippines which is 220 km due east which is also a fishing town.

B. History

A number of countries have made historic claims to the use of Scarborough shoal. China has claimed that a 1279 Yuan dynasty map and subsequent surveys by the royal astronomer Guo Shoujing carried out during Kublai Khan's reign established that Scarborough shoal (then called Zhongsha islands) was used since the 13th century by Chinese fishermen.

The shoal's current name was chosen by Captain Philip D'Auvergne, whose East India Company East Indiaman ship, Scarborough, was briefly grounded on one of the rocks on September 12, 1784, before sailing on to China.

The 2012 Scarborough Shoal standoff between Philippine and Chinese ships led to a situation where access to the shoal was restricted by the Chinese. However, in 2016, following meetings between the Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte and his Chinese counterpart, China allowed Filipino fishermen to again fish in the area.

C. Land reclamation and other activities in the South China Sea

The Scarborough Shoal (Panatag Shoal) and its surrounding areas are rich fishing grounds. Its lagoon provides some protection for fishing boats during inclement weather.

There are thick layers of seabird guano on the rocks in the area. Several diving excursions and amateur radio operations, and expeditions (1994, 1995, 1997 and 2007) have been carried out in the area.

At various times between 1951 and 1991, U.S. and Philippine military forces operating from Philippine bases routinely employed various types of live and inert ordnance at Scarborough Shoal for bombing exercises and other military training. It is possible that much of the unexpended ordnance remains on the ocean floor, posing a hazard to anyone attempting to disturb the shoal or the surrounding ocean areas. A CBS News report noted that fishermen here were more distressed by the pollution caused by the Masinloc thermal power plant and local barangay corruption than by any Chinese activities.

China, in recent years, has undertaken drastic efforts to dredge and reclaim land in the South China Sea to build artificial islands complete with infrastructure such as runways, support buildings, loading piers and satellite communication facilities. The island-building has prompted its neighbors and the United States to question whether they were strictly for civilian purposes, as claimed by Beijing. China’s island development has profound security implications. The potential to deploy aircraft, missiles, and missile defense systems to any of the new islands vastly boosts China’s power projection, extending its operational range south and east by as much as 1,000 kilometers (620 miles).

China’s highest rate of island development activity has been taking place on the Paracel and Spratly Island chains. Beijing has reclaimed more than 2,900 acres (1,174 hectares) since December 2013, more land than all other claimants combined in the past forty years, according to a U.S. Defense Department report. Satellite imagery has shown unprecedented Chinese activity on Subi Reef and Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratlys, including the construction of helipads, airstrips, piers, and radar and possibly surveillance structures[1].

In July 2015, Filipino fishermen discovered large buoys and containment booms at Scarborough Shoal and assumed them to be of Chinese origin. They were removed and towed back to the Philippine coast. In March 2016, in its Scarborough Contingency Plan, the CSIS Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative reported that satellite imagery had shown no signs of any land reclamation, dredging or construction activities at the shoal. Only one small Chinese civilian ship and two small Filipino trimaran fishing boats (bangkas) were seen, which was normal for the past few year.

In September 2016, during the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit, the Philippine government claimed that a number of Chinese ships capable of land reclamation had assembled at Scarborough Shoal. This claim was denied by Beijing.

Also in September 2016, the New York Times reported that Chinese activities at the Shoal continued in the form of naval patrols and hydrographic surveys. The Chinese navy restricted Filipino fishermen's access to the shoal from 2012 until August 2016, when Chinese authorities started to allow Filipino fishermen to resume fishing in the area after talks between Duterte and Chinese officials.

In January 2017, the International Business Times reported the possibility of land reclamation at Scarborough Shoal by China. However, photos of the shoal posted by CSIS have, to date, not shown any evidence of reclamation activity[2].

D. Importance of West Philippine Sea (WPS) to the Filipino Fisherfolk

According to a group of marine experts, Hazel Arceo et al., the WPS has been and remains as one of the most important fishing grounds in the Philippines, with substantial contribution to the national economy and to the social and economic well being of coastal communities along its margins and even beyond its geographical extent. WPS is part of Philippine territory (P.D. 1596 and R.A. 9522). The WPS is composed of living shallow coral reefs with extensive marine biodiversity that support productive fisheries. (KIG---Kalayaan Island Group---comprised one-third of the total coral reefs in the Philippines). Besides being host to a rich marine biodiversity, coral reefs are considered to be one of the most productive marine ecosystems.

Scarborough Shoal, or Panatag Shoal, is a popular traditional fishing ground within the Philippine EEZ. A recent study showed that Scarborough Shoal could produce as much as 31 metric tons of fish per sq km of coral reef per year. Healthy coral reefs closer to the mainland could produce between 15 and 20 metric tons per sq km per year (Alcala Ac, Russ G. 2002, Status of Philippine Coral Reef Fisheries, Asian Fisheries Science 15.177-192). Scarborough Shoal has shallow coral reefs and sand where fish abound. There are deep areas inside the shoal’s lagoon where commercial fishing boats can go into for protection during stormy weather. The fish found in the area include talakitok, lapu lapu, tarian, mulmol. There are also giant clams, large crabs, lobsters and other types of shells and mollusks.

Scarborugh Shoal is tiny compared to the entire KIG. Coral reefs in the whole KIG can potentially provide around 62,000 to 91,000 metric tons of fish per year. (Arceo Ho, Cabsan et al. 2020, Estimating the potential fisheries production of three offshore areas in the WPS, Philippines, Philippine Journal of Science, 149.647-658). This volume of fish could supply the yearly fish needs of 1.6 million to 2.3 million Filipinos.

Fifty-five percent of global marine fishing vessels operate in the South China Sea (SCS) and about 13-21 percent of annual global marine fish catch worth at least US$1.8 billion comes from SCS. Cumulative catches from 2000 to 2014 show that 27 percent of total marine capture fisheries production in the Philippines comes from the WPS, while the estimated fisheries production from coral reefs in the KIG could potentially contribute another 3-5 percent to the total Philippine marine fisheries production.

With one-third of the total marine fish catch in the country coming from this region, government officials should refrain from downplaying the importance of the WPS as a major fishing ground and an important source of fish for the Filipinos.

Considering that 30 percent of total protein intake and 70 percent of the total animal protein intake by Filipinos come from fish, it is important that our fishers have unrestrained access to the productive fishing grounds in the WPS.

BIGKIS Fisherfolk leaving for Scarborough Shoals

The Filipino fisherfolk

Besides its contribution to food security, marine fisheries in the WPS provide employment to about 1.8 million people, most of whom are in the small-scale fishing sector.

Poverty incidence in the country is 16.6 percent (2018), or 17.6 million families, living below the poverty line of P10,727.00. The fisherfolk have the second highest poverty incidence (26.2 percent per 2018 data) among the basic sectors, next to farmers (31.6 percent) in the Philippines. The fishers are also part of the 13.6 percent (3.4 million) Filipinos who are experiencing hunger in the country.

They are the most marginalized among the vulnerable sectors who live mostly in hazardous areas like the mangrove forests, rivers and coastal zones. Although, they build their own shelters, most rent the land from other villagers, paying monthly rentals ranging from P500 to P5000. Although they try with all their might to uplift the lives of their families, this task seems impossible to achieve as they sink deeper into poverty and hunger due to the situation not only in the WPS but also in the rest of the country.

The fishers’ dire living condition parallels the hardships they experience at sea. They face inhospitable weather in the open waters, being beaten by the scorching sun during the dry season or the fury of the sea during the monsoon, and the cold nights while separated from their families for days or weeks. Their sole consolation is that they can bring home enough fish catch for their families to survive for a week or two until they go out to the sea again. However, the Chinese prohibitions and virtual blockade in parts of the WPS, particularly Scarborough Shoal, and the lack of protection from the Philippine government are reflected in their dwindling catch. This has been the experience of the fishermen from Zambales and Pangasinan.

Zambales is the coastal province nearest to the shoal with a distance of about 120 nautical miles (222 km). Pangasinan is directly north of Zambales.

Zambales, which is part of Central Luzon, is composed of 13 municipalities. One of these is Masinloc, where the majority depend on fishing in the WPS. They are largely marginal fishermen.

Barangay Inhobol in Masinloc has two Sitios. The sitios of Balogo and Matalvis are the biggest fishing communities in Masinloc. Most of the people are migrants from Visayas and Mindanao. Sitio Matalvis has a population of about 1,000. The men are small or marginal fishers or serve as workers or crew in commercial fishing vessels that fish at the WPS.

In the province of Pangasinan, the biggest fishing village is in the municipality of Infanta, in Barangay Cato. The village has 400 fishers who serve as workers, crew members called “pasaheros” in about 100 commercial fishing boats owned by Filipino or foreign capitalists.

Each commercial fishing vessel can carry 3-5 small fishing boats. This vessel is usually owned by the big capitalist in the municipality. These commercial fishers use “payao,” or artificial floating reefs, where they harvest the fish after a certain period. The fish catch from the payao are brought to the commercial fishing boat (called “carrier”). Separately, small boats with the pasaheros are hoisted down to the water and using traditional fishing gear of hook and line or spear, they also contribute to the fish catch. The fish caught include galunggong, talakitok, barilyete or tuna, and “isdang bato” (like loro tarian).

BIGKIS Ng Mangingisda Federation

This is the federation of fisherfolk (both municipal and plying the WPS) from Zambales, Pangasinan, Bataan, and Coron, Palawan, composed of more than 6,000 members whose aim is to protect and defend their fishing rights in the maritime regimes of the Philippines. Rony Drio is the spokesperson of BIGKIS.

China’s Violation of the Right to Adequate Food of Filipino Fishermen in Panatag Shoal (Scarborough Shoal)

The territorial dispute in the South China Sea has had a detrimental impact on thousands of small Filipino fishermen – those who venture out to sea on their own and those who work for fishing fleets. The government has not released any figures on the total number of fishermen affected by the Chinese blockade of their traditional fishing grounds. The dispute is rooted in China’s claims over all of the KIG or Spratly Islands and almost the entire South China Sea, including waters close to the western parts of the Philippines.

It was in June 2012, that the Chinese coast guard first forced a group of Filipino fishermen to leave one of the Scarborough Shoal. The Filipino fishermen reported that Chinese coast guard vessels fired water cannons at them as they tried to venture close to the shoal. In 2013, the Philippines filed a case challenging China’s nine-dash-line claim over nearly all of the South China Sea, before the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. In July 2016, the arbitral tribunal that was established to hear the case decided in favor of the Philippines, junking China’s claims.

According to Leonardo N. Cuaresma, President of the Nagkakaisang Mangingisda ng Panatag/Bajo de Masinloc (United Fishermen of Bajo de Masinloc) and member of the Pambansang Koalisyon ng Karapatan sa Lupa (PKKL), they freely fished in the rich fishing grounds of Scarborough Shoal. Fishermen from neighboring countries also go there to fish unmolested by the Philippine government. During those times, all fishermen could fish in the area peacefully. That rich fishing ground brought stability to the lives of the fishers. They had a stable income, their families had enough food to eat, they could send their children to school. The sea provided enough livelihood for them to have a stable income. The fishers of Masinloc also supplied fish for the whole of Zambales. However, their lives started to become miserable after the Chinese government prohibited them from fishing at Panatag.

Elsa Novo, president of PASAMAKA-L in Zambales, one of the people's organizations (POs) of the Peoples Development Institute (PDI) that is working closely with the fisherfolk of Masinloc town, said that just after the favorable decision of the arbitral tribunal, Chinese coast guard ships patrolling the shoal fired at Filipino fishermen who attempted to fish in the waters near Scarborough. The Chinese showed complete disregard for the tribunal’s decision. This Chinese blockade led to hunger and impoverishment of the families of the fishers of Masinloc.

China’s actions have undermined the livelihood and the food needs of poor fishermen from Zambales, Pangasinan and other western Philippine provinces. “They did not overturn just one pot, but many pots. So many families will go hungry because of what they are doing,” one fisherman said in describing the outcome of China’s blockade. In Masinloc town alone, about 3,000 fishermen were unable to fish at Scarborough Shoal for four years. From tons of catch from Scarborough, now the fishermen are lucky if they are able to bring home a few kilos from the waters close to their town. Other fishermen caught or raised aquarium fish to sell to pet shops in Manila as an alternative source of income.

Meanwhile, the Chinese were building islands by reclaiming land from reefs in the Spratlys to bolster its claims over the territory. They have raised up from the sea at least seven islands where none existed before. One of the biggest reclamation works included a 3-km runway that could handle all kinds of Chinese military and civilian aircraft. Chinese officials say the islands are for scientific or peaceful uses such as refuge for fishermen during bad weather, but their potential military use exists. Recent satellite pictures show dozens of Chinese fighter jets parked on these artificial islands. With their air and naval assets already in position, the Chinese could impose more restrictions on maritime and air travel around or over these new islands, effectively extending its territorial reach hundreds of kilometers from their homeland. As mentioned above, aside from being a rich fishing ground, the Spratlys are believed to sit atop gas and oil deposits, and straddles one the world’s busiest sea lanes.

The Permanent Court of Arbitration Ruling

In January 2013 the Philippines formally initiated arbitration proceedings against China’s claims, also known as the “nine-dash-line,” including the Scarborough Shoal, which the Philippines argued was unlawful under the UNCLOS. An arbitral tribunal was constituted under Annex VII of UNCLOS and it was decided in July 2013 that the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) would function as registry and provide administrative duties in the proceedings.

On July 12, 2016, the tribunal agreed unanimously with the Philippines. In its award, it concluded that there is no evidence that China had historically exercised exclusive control over the waters or resources, hence there was “no legal basis for China to claim historic rights” over the area within its nine-dash line. The tribunal also ruled that China had caused “severe harm to the coral reef environment” and that it had violated the Philippines' sovereign rights in its exclusive economic zone by interfering with Philippine fishing and petroleum exploration through, among others, the restrictions it had imposed on the traditional fishing rights of Filipino fishermen at Scarborough Shoal. China rejected the ruling, calling it “ill-founded.” Chinese President Xi Jinping insisted that “China's territorial sovereignty and marine rights in the South China Sea will not be affected by the so-called Philippines South China Sea ruling in any way.” Nevertheless China would still be “committed to resolving disputes” with its neighbors, he said.

Chinese Ship encroaching in the Scarborough Shoals

problems and issues encountered by the fishers

Issue 1: How to deal with the almost depleted aquatic resources in the municipal waters of Zambales.

The depletion of aquaric resources hvae been caused by proliferation of fishpen and fish cages. Owned by foreign capitalists mostly Chinese or local elites. Mangrove forests are destroyed by the construction of a coal-fired power plant and wharves, and the establishment of mining operations in Zambales and Pangasinan, that had sent silt and mud out to the sea from the mountains. The feeds for the fish in the cages (typically bangus or milk fish) have also caused pollution, which depleted oxygen in the water, resulting in fish kills. People also are getting skin diseases from the chemical contamination of the water from the mine waste.

In 1989, fishpens started to sprout in Oyen Bay in Masinloc. By 2000, these fishpens have been replaced by fish cages owned by foreign capitalists, mostly Chinese who use dummies (e.g. Mani Co) or local elites (e.g. Hilario, Estrada, etc.) who have the money to spend about P100,000 for one fish cage. That amount is in addition to what is spent for maintaining the fish cages. These fish cages now proliferate from Palauig to Masinloc municipalities in Zambales due to a program under the Agricultural Fisheries Modernization Act (AFMA) of the Department of Agriculture (DA). The fisherfolk can no longer fish in the municipal waters because of the presence of fish cages. The fish cages also block some passageways going to the open sea. In 2003, more than 1,000 small fishermen protested against fish cages in Masinloc in a fluvial parade supported by other sectors. They presented their grievances to the municipal council. However, their sentiments were not heard and until now there is a continuous expansion of fish cages in the province.

The mangrove forests, which are home to crabs and seashells, have also been destroyed to make way for more fish cages. As a result, fishing areas where clams and corals that serve as home to fish and other marine life, have been occupied by the cages. Seaweeds and other marine plants, crabs and corals are overwhelmed by feed waste that turn into silt and mud.

All these cause the fish catch to go down. Before, a fisher could get 30 kilos of clams per catch now, he only gets five kilos of “reject” quality. Worst, their health was affected because of the water contamination. This condition pushed the marginal fishers to go out to other areas farther away to fish, resulting in higher costs (in fuel, ice, meals at sea) but with minimal returns.

On June 22, 2018, the Masinloc Oyon Bay Protected Landscape and Seascape under R.A. 11038 was passed into law. It turned 7,558 hectares of waters into protected areas in Masinloc and Palauig. It established a Protected Area Management Board (PAMB) consisting of the DENR, BFAR and LGU and fisherfolk representatives. But the PAMB has been weak and could not prevent the expansion of the fish cages in Zambales.

In 2018, Chinese vessels named Hornet 1, Hornet 2, Hammer 9, Hammer 10 and Pacific No. 9 started dredging the waters in Oyon Bay. The dredging caused additional hardship to the fishers as the Oyon Bay was the remaining fishing area in Masinloc and Palauig. This 2021, two more Chinese dredging vessels were added --- Zhonghai 69 and another with Chinese characters which the fishermen could not read.

The local government allowed the dredging by the Chinese and passed ordinances that made it difficult for small fishermen to access marine resources in the municipal and territorial waters.

A wharf was built in barangay Cato and another wharf/pier is being built in barangay North Lucapon in Sta. Cruz, Zambales, owned by the barangay chairman.

A nickel mine is being operated on a mountain ridge in Cato, a while the WestChinaMain is operating a ferro-nickel plant and mining project in Candelaria, Zambales.

Issue 2: How to ensure fishing rights in the WPS in the face of Chinese aggression against Filipino fisherfolk.

- Incidents of China’s aggression against Filipino fisherfolk

The first recorded incident was said to be on Feb. 25, 2011, when three Philippine fishing vessels that were sailing along Jackson Atoll were approached by Chinese vessels, announcing through their ship radio that the area was Chinese territory and telling the Filipino fishing vessels to leave immediately or they would be shot. Other incidents were reported --- Filipino shipping vessels being driven away, Chinese occupying islands, Chinese vessels continued presence until May 2011. On May 24, 2011, an alarming activity in the South China Sea was spotted by Filipino fishermen. In an AFP report, they saw Chinese ships unloading construction materials and erecting posts and deploying buoys near the islands.

In 2012, the Chinese Coast Guard (CCG) prohibited Filipinos from fishing at Scarborough Shoal. The Filipinos were chased away by the CCG and bombarded by water cannon. As a result Filipino fishermen grew scared of the CCG and stopped fishing at one of their traditional fishing grounds.

In 2018, three fishermen, Jurry Drio, JR Ermita Jr. and Delfin Egana, were aboard their small boat fishing near Panatag Shoal when men from a Chinese coast guard speed boat harassed them and ransacked their cooler. The Chinese took all the big and expensive fish that the Filipinos had caught, leaving as “barter” cigarettes, water, liquor, bread and expired canned goods. This reported intimidation and harassment reached Malacanang, which called the three fishermen to make a statement about their experience. However, presidential spokesman Harry Roque downplayed the incident and said to the press that only a barter exchange occurred between the CCG and the Filipinos.

The Department of Foreign Affairs filed a diplomatic protest against China after the CCG allegedly confiscated the fishing gear of Filipino fishermen near Panatag Shoal in May 2020.

The latest display of China’s aggressiveness toward Filipino fishermen took place on January 26, 2021, when a fisherman who was sailing to the sandbars near Pag-asa Island was blocked by a CCG ship, preventing him from approaching the sandbars.

Giant clams have also been harvested by the Chinese from Panatag Shoal and in the process destroyed coral reefs in the area.

Fish Cage in Masinloc, Zambales

effect and impact on filipino fishers and communities

While China expands and tightens its hold over the West Philippine Sea, despite the arbitral award that invalidated China’s claims to nearly the entire South China Sea, the fishing industry has been bearing the bigger brunt of the dispute as it continues to experience losses. The continued presence of Chinese vessels and the constant blocking of Filipino fishermen have affected both the fishing industry and the livelihood of Filipino families who depend on the sea for their livelihood.

-

Environmental destruction

The destruction of the coral reefs in the West Philippine Sea negatively impacts the fishing industry and can cost an estimated 3 million fishermen their jobs[1]. A National Geographic article explained that the destruction of reefs can be detrimental to the marine ecosystem because when reefs are destroyed, the fish living there lose their habitat and an important source of food[2]. The fish will abandon these areas and look for other reefs to inhabit. Damaged reefs mean less fish to catch and can ultimately lead to the collapse of the fishing industry in Zambales and Pangasinan.

Mine tailings cascading down from the mountains contaminate the rivers, lake and the municipal waters, killing the fish and other living resources. Farmers, too, are affected as agricultural land become parched and acidic.

-

Economic Impact: Loss of livelihood

The marginal fishermen and their families suffer further hunger and impoverishment from the Chinese encroachments. Before the Chinese incursions, according to Pangasinan fisherman Christopher De Vera, their catch reached 2-3 tons of various type of high value fish. After the CCG and Chinese militia prohibited them from fishing in the Philippines’ own EEZ, their catch had dwindled. Ten days at sea can only earn them about P150,000. From that total amount, the capital (fuel, ice for preserving freezing the fish, food and water for 12 workers and crew members) amounting to P50,000 will be deducted. The remaining P100,000 will be divided between the boat owner and the 12 crew members and workers. Fifty percent, or P50,000, goes to the owner. The remaining P50,000 will be divided among the 12 men, each one getting only P4.166.00 for his labor. Usually, these crew members/workers also owe the boat owner in cash advances of at least P2,000 that they leave with their families before they go out to sea. After paying the loan, a fisherman is left with P2,166 to be used to buy a half sack of rice worth P1,050, and to pay the sari-sari store where his family made purchases on credit. They also have to pay for house rent. After all the payments, the fishermen are left with almost nothing, hoping that their families can survive until their next fishing venture.

Pasaheros bring their own small fishing boats on large commercial fishing vessels. One of them, Rony Drio, said that his catch would be weighed by the head of the crew who sets the amount of P40-50.00 per kilo for high-value fish like lapu-lapu. Drio brings home at most P6,000.00 after 10 days at sea. Paying his cash advances to the boat owner leaves him with P4,000. After buying a half sack of rice, he has P2,950 remaining to use to pay his debt to the sari-sari store. His house rental payment also leaves him almost cashless. Both the crew/workers and the pasaheros are disallowed from taking even a single fish as they are paid in cash. All the fish caught is owned by the capitalist.

According to fisherman Vicente Paluan, his family cannot afford a home of their own, or pay for their health care nor his children’s education, clothes and proper diet and nutrition.

Due to the travel prohibition during the pandemic lockdown, the fish catch cannot be transported to Manila. It is sold at a very cheap price to traders.

-

Social Impact: Psychological trauma

Most of the fishers who had gone to the West Philippine Sea and who experienced harassment and intimidation from the Chinese, have developed psychological trauma. Some abandoned fishing and do not want to go out to the sea at all. Others like JR Ermita live in constant fear, afraid for his life. Delfin Egana cannot venture out to the waters because every time he sees a ship, he panics and has an anxiety attack. The deep-rooted impact on the psyche of these fishermen, who feel that they were abandoned by the government and left on their own at the height of the conflict in the WPS, paralyzed them into inaction after the Chinese fired water cannon at them, and chased, harassed and intimidated them.

-

Political Impact:

There was lack of governance over the natural resources in the WPS because of the ongoing conflict.

In 2016 during the Presidential Elections, President Rodrigo Duterte promised to fight for Philippine sovereign rights in the West Philippine Sea even promising that he would jet ski to an island held by the Chinese and plant the Philippine flag[3]. Five years have passed and the President has yet to fulfill that promise. What the Filipino people was told, instead, by the President himself was that China has possession of the WPS and that we cannot do anything about it[4]. He said his jet ski statement was just a joke and part of election campaign “bravado,” and that anyone who believed him was “really stupid.” Over the years, critics of the President have been saying that he has become subservient to China.

BIGKIS, the fisherfolk federation in Zambales and Pangasinan, is demanding that the Philippine government respect and protect their fishing rights. They urged the national government to adopt a more assertive and responsive pro-Filipino approach in the WPS and to enlighten the public on the critical role of these waters for ecological resilience, food security and sustainable development.

Reclaiming and gaining possession the WPS and the Philippine EEZ could expand our economy and also create more jobs not just for fishermen but other Filipinos as well, once the country is able to open up opportunities to different industries linked to marine resource exploration and exploitation. In short, Filipinos want their government to put their greater interest as the top priority.

The government should level up its efforts in reclaiming what is rightfully ours by asserting Philippines sovereign rights over the West Philippine Sea. But first and foremost, it must have a definitive and clear stance on the maritime dispute with China. President Duterte’s administration has been spending a huge chunk of our budget on military upgrades[5]. Therefore, increased military presence in the West Philippine Sea should be done soon and authorities patrolling our waters should be on the lookout for illegal fishing and exploration activities. With the pandemic and millions of Filipinos losing their jobs and suffering from hunger, having a proactive government that will protect and defend the rights of all Filipinos is critical to the well-being of our country and the future generations.

Problems-Facts Group Discussion of BIGKIS Fishermen in Cato, Infanta, Pangasinan

conclusion

The fisherfolk of BIGKIS demand the following:

General:

Support the call of the Filipino fisherfolk to respect, protect and defend their fishing rights in the maritime regimes in general and in the WPS in particular.

Specific:

First, Implement the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea UNCLOS) and the arbitral ruling in order to bring back the usual fishing activities before the Chinese aggression started by enforcing the ruling of the tribunal;

Second, the fisherfolk should be protected by the Philippine Coast Guard and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources (BFAR) when at sea.

Third, demand that the Chinese government apologize and provide reparation for the crimes committed against the Filipino fishermen. China, under the United Nations-Economic Social and Cultural Rights (UNESCR), has an extra-territorial obligation to the Philippines to repay all the accumulated damage to the environment such as the destruction of the coral reefs at Panatag Shoal.

Fourth, raise the fisherfolk issues specifically on economic and environmental degradation to the Supreme Court and bring the territorial disputes to an international body for conflict resolution.

The Philippine government, in fulfillment of its duty to promote and protect the right to adequate food, must take all steps to ensure that Filipinos regain access to these rich fishing grounds. Its duty extends to exhausting diplomatic means to facilitate access to our waters.

Systemic hunger and poverty prevails in the Philippines. The inadequacy of the Philippine response has led to the high levels of hunger and poverty.

Lastly, develop a comprehensive, action-oriented program for the small-scale fishermen.

While the bigger part of the responsibility falls on the Philippine government, civil society has its share of responsibility, too. Civil society must be vigilant and engage the government. There is the pressure that civil society must bring to bear upon the government so that it will do what is required. Conversely, the government has a good faith duty to collaborate with civil society in the effort to end hunger and poverty.

We call on both the government and civil society to perform their roles to promote and protect the right to adequate food for all.

We invite all concerned to pause and reflect on the depths of the problems of hunger and poverty in the Philippines, to reverse past decisions harmful to the right to food, and make new ones that step up rather than reduce protection for the right to adequate food. Today’s period of hunger in the Philippines is a dark one. There is a need promptly to craft a law for the fishers rights in the WPS similar in nature to the zero hunger bill being offered and to follow through immediately with its implementation.

bibliography

Areglado, Juan. Kalayaan: Historical, Legal, Political Background. Manila: Foreign Service Institute, 1982.

BALAI, Asian Journal, II No. 2.

Bulletin Today. June 15-July 25, December 1-15, 1982.

Bureau of Energy Development, Ministry of Energy (RP). Nido Oilfield: First in the Philippines. Manila: BED, 1977.

Cabinet Committee on the Law of the Sea (RP). Case Study: Kalayaan Island Group Dispute (Unpublished).

____________. The Kalayaan Islands (Prepared by the ministry of National Defense) October 1982.

____________. “National Marine Interests of the Philippines in Contrast with her Neighboring Countries” SEG on Resource and Industry Kit (Unpublished).

Chang Pao-Min. “The Sino-Vietnamese Territorial Dispute,” Asia Pacific Community (Spring 1960) 130-165.

Development Academy of the Philippines-Ministry of Natural Resources (RO). Jurisdictional Claims and Agreements, Disputes and Settlements (Unpublished).

Drigot, Diane C. Interest in Oil as a Factor in the Philippines’ Claim and Disputes over Marine Territory in the South China Sea. EWEAPI, Hawaii: August 1980 (Pre-publication).

Du Bois, Ernest P. “Hydrocarbons and the South China Sea,” Proceedings of the Fourth Regional Conference on Geology. Mineral and Energy Resources of Southeast Asia. Manila, November 18-20,1981.

Hatley, Allen G. “The Nido Reef Oil Discovery in the Philippines” Its significance,” Proceedings of the ASCOPE Conference. Jakarta, October 11-13, 1977.

Heinzig, Dieter. Disputed Islands in the South China Sea. Weisbaden: Institute of Asian Affairs in Hamburg, 1976.

Hungdah Chiu and Choon-Ho Park. “Legal States of the Paracel and Spratly Islands,” Ocean Development and International Law Journal (1975) 1-28.

Hungdah Chiu. “Legal States of the Paracels and Spratly Islands.”

La Grange, Carolyne. South China Sea Disputes: China, Vietnam, Taiwan and the Philippines, Hawaii: EWEAPI, May 1980.

Levorsen, A.I. Geology of Petroleum. Bombay: Vakil, Feffer and Simons Pvt. Ltd. and W.H. Freeman and Co., 1970.

Park, Choon-Ho, “South China Sea Disputes: Who Owns the Islands and the Natural Resources,” The Journal of Marine Affairs, V (1978) 27-59.

Perfecto, Isidoro Jr. T. “The Philippines’ Kalayaan Island,” FSI Record I (June 1980) 29-51.

Porth, H.A. Glocke and R. Monzon. The Oil/Gas Prospects of the Reed Bank Area. Manila: Bureau of Energy Development. September 1978

Prescott. J.R.V. Maritime Jurisdiction in Southeast Asia: A Commentary and Map. Hawaii: EWEAPI, 1981.

____________. “Maritime Jurisdiction Issues”. (Unpublished)

Siddayao, Corazon Morales. The Offshore Petroleum Resources of Southeast Asia. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Shit Ti-Tsu, South China Sea Islands, Chinese Territory Since Ancient Times”. Peking Review (12 December 1975) 10-15

United States Department of Energy. OTEC Thermal Report for Manila P.I. May 1979

Valencia, Mark J. Proceedings of the Workshop on Coastal Area Development and Management in Asia and the Pacific. Manila, December 3-12, 1979. Honolulu: University Press of Hawaii, 1981.

_____________. Shipping Energy and Environment: Southeast Asian Perspectives for the 1980’s. Workshop Report, December 10-12, 1980. Honolulu: East-West Environmental and Policy Institute, August 1981.

Velasco Geronimo Z. “Philippine Offshore Oil Exploration/Exploitation of Activities: Its Impact on National Development.” Proceedings of the Second PN Sea Poer Symposium. June 20-21, 1979.

Vietnam Courier. “The Hoang Sa and Truong Sa Archipelagoes (Paracels and Spratly).” Hanoi 1981.

Villa, Rod Jr. “Kalayaan-Farthest Outpost”, Philippine Panorama. May 30, 1982, pp.16-22.

Yorac, Haydee B. “The Philippine Claim to the Spratly Island Group: Issues and Problems” (Mimeographed).